Since the passage of SB 411 in 2022, more and more counties in Indiana are creating or updating their local ordinances concerning commercial solar farms. This bill established guidelines for siting wind and solar projects, but it is entirely voluntary – it is up to the counties whether they want to be considered solar or wind ready communities.

This summer, as a McKinney Climate Fellow from the O’Neill School at IU Bloomington, my job for ILPA was to do research regarding commercial solar in Indiana. My original project was to create a model template solar ordinance for local governments, but that had already been expertly done by IU’s Environmental Resilience Institute and can be found here. I decided to take the project in a different direction after noticing how much pushback solar was getting in many counties. Much of this resistance was due to the loss of farmland, but environmental concerns regarding wildlife, native plants, and erosion control were also common.

Considerations for Advancing Solar and Conservation in Indiana

Renewable energy infrastructure impacts ecosystems

The major ways that solar can affect native habitats and biodiversity are through vegetation, wildlife habitat, and wildlife connectivity. Solar farms, especially those that are located on what was previously agricultural land, have the opportunity to plant native vegetation around and underneath panels, as well as in buffer areas. This would also benefit developers – once established, native vegetation requires less upkeep than non-native turf grasses. They also have the ability to provide wildlife habitat through bird and bat boxes, and small woodpiles for reptiles.

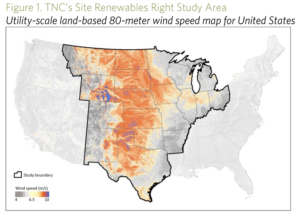

One of the ways that these installations can most impact wildlife is simply by affecting its ability to move. Some projects can take up thousands of acres, which can block migration paths or cut territories in half. The best way to prevent this is to not build in critical migration paths or habitats, such as those shown in the Nature Conservancy’s Site Renewables Right tool. Another is to incorporate wildlife-friendly fencing, which can be as simple as having an eight-inch gap at the bottom of the fence, or incorporating small mammal gates. If solar farms are built near known wildlife corridors, some areas should be built without fencing in order to serve as passages for larger wildlife.

Over half of Indiana counties have a solar ordinance in effect – what do counties require?

During my research, I found that sixty-two of Indiana’s ninety-two counties have a solar ordinance in effect. When looking into utility-scale solar requirements, I looked at several categories: consultation regarding wetlands/wetland delineation, restoring native and/or pollinator-friendly vegetation, wildlife-permeable fencing, wildlife corridors, erosion control, and decommissioning plans. The full inventory of my findings is available upon request.

I found that native and/or pollinator-friendly vegetation requirements were fairly popular, with almost half of the ordinances requiring it. Wildlife-friendly fencing and wildlife corridors were much less so, with only nine and four ordinances respectively. Erosion control is generally required through other permits or ordinances, but about two-thirds of the ordinances still specified some sort of related requirement in them. Wetland delineation is similar in its requirements, and was mentioned in less than half of the ordinances. Nearly all of the ordinances had decommissioning plans, with many of them being the most detailed part of the ordinance.

How solar farms are incorporating habitat friendly practices

Native and pollinator-friendly aspects have already been incorporated into several notable solar farms. Randolph County was the first to create an ordinance with these provisions in 2020, ahead of the county’s Riverstart Solar Park. St. Joseph County’s Honeysuckle Solar Project is another example of solar farms incorporating pollinator-friendly landscaping, and is working to incorporate commercial honey production into the farm as well. Honeysuckle is working with the Bee & Butterfly Habitat Fund in the “Solar Synergy” program, which aims to provide solar developers with seed mixtures, carbon sequestration and habitat monitoring, and commercial beekeeping connections.

Currently, there is little in the way of wildlife-friendly fencing and wildlife corridors in Indiana’s solar farms. Lightsource BP, the developer behind the Honeysuckle Solar Project, has a document which outlines how they are incorporating wildlife-friendly fencing and other biodiversity protections, but there is no indication on their website on what has actually been implemented on specific projects. The largest project currently in the works in Indiana is Mammoth Solar, a 13,000-acre farm that will be located in Starke and Pulaski counties. Both counties have native vegetation provisions, but only Pulaski has one for wildlife-friendly fencing. For now, it is unclear how this will affect the project.

The future of solar development in Indiana

In 2021, Purdue University Extension conducted a survey of the existing solar and wind ordinances in Indiana. They looked at many more standards than my project, including setbacks and buffers, noise limits, glare standards, and maintenance plans. Since that study, nine counties have written and passed new ordinances, and four more are either currently writing them or have them in moratorium while further discussion occurs. With the passage of SB 411 and with more, larger solar projects coming into the state, that number will increase. It is likely that already existing ordinances will be updated in the near future to prepare for the possibility of large solar developments as well, and local governments should be encouraged to include provisions that protect the local environment.

Large solar farms are likely to become more common all over Indiana, and it is vitally important that counties start preparing their related ordinances. A detailed ordinance can help not only establish environmental protections but agricultural and aesthetic protections as well. Having an ordinance prepared before being approached by developers can help ensure that advances in renewable energy move forward while still prioritizing the needs of Indiana residents, both human and otherwise.

By Gabrielle Robles

McKinney Climate Fellow

In the summer of 2023, Gabby worked with Indiana Land Protection Alliance to examine how the growing renewable energy industry could impact land conservation. She evaluated Indiana county solar ordinances and identified best practices and considerations for advancing renewable energy, while also achieving land conservation goals.